One of our five guiding principles at Vervint is to serve our teams and clients with humility. Yet we certainly take pride in the work that we do. We’re proud of the culture we’ve built here. But can beliefs about our own efficacy get in the way of achieving positive results for the organizations we serve?

If so, we may tip over the edge of healthy, grounded appreciation into hubris. The term hubris came into English from ancient Greek, and it is typically associated with tragedies. A character loses sight of reality because of their pride, and it brings about some (often unnecessary) calamity. Faustus, who already fancies himself a genius, makes a bargain with the devil to become superior to everyone else — only to ultimately be dragged off to eternal damnation. Doctor Frankenstein defies the natural order and creates life — only to have his creation murder his brother and wife and wreak other tragedies on his life.

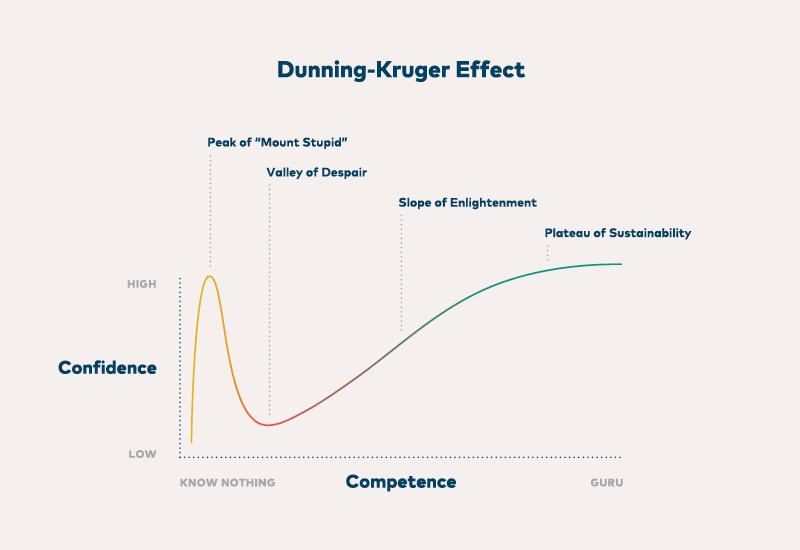

This sentiment of pride coming before the fall may have its roots in our basic psychology. A classic example is the Dunning-Kruger effect. People overestimate their abilities in spite of having little experience and knowledge — only to crash down to reality as they gain more training and education.

The title of Dunning and Kruger’s original 1999 article sums up the core sentiment nicely: “Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments.” In describing their findings, Dunning and Kruger explain that “incompetence, like anosognosia, not only causes poor performance but also the inability to recognize that one’s performance is poor. Indeed… participants in the bottom quartile not only overestimated themselves, but thought they were above average” (42).

Often, individuals ascending what is colloquially known as the “Peak of Mount Stupid” make erroneous decisions and other mistakes based on their incomplete knowledge. This idea, that the pride we have in ourselves can ultimately betray the outcomes we’re striving for, isn’t a new one, and it isn’t unique to individuals. It can creep and engulf entire organizations.

The Dangers of Founder’s Syndrome

Broadly, founder’s syndrome (or “founderitis”) occurs when the founder of an organization (or project) has a disproportionate amount of influence and power that creates problems for the team. Examples vary from company to company, but some of the symptoms associated with founder’s syndrome include the following:

- The founder makes decisions without input from others and outside of established processes.

- Similar problems recur over and over at the organization.

- Team members are hired based on their relationship to the founder, perhaps despite a lack of skill, experience, or alignment to values.

- The founder’s ideas and decisions typically win out, even over better alternatives.

- The founder faces difficulty adapting as the organization grows.

- Those who challenge the founder’s approach, ideas, etc. are ignored or removed.

Perhaps the most ironic aspect of founder’s syndrome is that many of the traits that make a founder (and business) successful early on (risk taking, operating on the fly, saying “yes” to anything, individualism, etc.) end up becoming liabilities as the organization matures.

The Dangers of Monoculture

On paper, a monoculture centered around a founder’s vision can seem like a positive thing for an organization. Everyone shares the same values. Everyone is working toward the same goals. Everyone is contributing to the same company culture. This can seem like an extraordinary alignment of purpose and approach — especially when everything is perfectly in line with what a founder or leader expects and desires.

But monoculture is a sure sign of organizational weakness.

Creative ideas, innovation, novelty, breakthroughs, adaptability, agility, and progress don’t magically appear from the font of a founder’s reservoir of genius. They are derived from diversity of thought and experience.

The unfortunate truth is that confirmation bias and its consequences can look a lot like “alignment.” And one day, your organization may suddenly arrive at a destination, only to realize that you were driving west and, all the while, the world was growing eastward.

The Solution to Founder’s Syndrome and Monoculture: Collaboration, Diversity and Humility

At Vervint, a few of our values seem to get most of the press:

- Honor our employees and their families first, clients second, and the rest will fall into place.

- Delight our clients with every touchpoint.

- Embrace innovation and entrepreneurship.

But another one of our values, “Serve our teams and clients with humility,” is the counterweight to these. It is the recognition that none of us has arrived, that we are flawed beings and that serving one another acknowledges that there are times others will have a place of prominence. Serving with humility is not something one can impose or demand — because doing so would be a stunning display of a lack of humility. One who is serving with humility knows that honoring the whole, doing good for others and elevating them serves a higher purpose.

Serving with humility (coupled with our final value: Learning though curiosity and empathy) also helps to acknowledge our intellectual fallibility. None of us has all the answers. None of us has a complete and perfect understanding of the solution or even the problem we are trying to solve inside Vervint or for our clients. Therefore, it is incumbent on us to be open to new information and listen to other people’s ideas. To listen hard. To ask questions and, even more difficult, receive questions believing that an honest critique can lead to a better outcome.

16: Scaling Culture

I was speaking to a group of interns recently, and I learned something about our work that I didn’t know before. I am past the point of any degree of relevancy in writing code for a client engagement, but I learn every day from the people that do. Truly, one of the great things about being at Vervint is the opportunity to learn from wonderful, highly capable people across disciplines and in various stages of their careers as they work in different ways to delight our clients.

And so we serve. And so we learn. It requires humility and empathy and curiosity.

And when you do these things well, guess what? It makes people feel honored and valued. It makes delighting our customers a team sport, not an individual one. And collectively we can innovate quickly and provide immense value to our customers in ways that they (and sometimes even we) never expected.

How Else Can We Combat Founder’s Syndrome and Monoculture?

Our core values are a hedge against monoculture here at Vervint, but what specific actions can leaders in an organization take to foster diversity, dialogue, and innovation?

Here are a few suggestions:

- Let others shine within the organization. Throw the spotlight on others, delegate important work, provide autonomy (especially when it comes to decision-making) and consider taking some (probably well deserved) time off.

- Create a succession plan.

- Create a communication plan that others can follow to increase transparency and ensure that information reaches everyone who needs it.

- Develop a clear mission statement. This creates a touchstone for mission-focused and mission-driven decision-making.

- Walk into every interaction with the fundamental assumption that you’re there to learn something new.

- Make diversity a priority in the hiring process: diversity of thought, diversity of experience, diversity of opinion, etc.

- Implement ways to gather anonymous feedback from all employees, like a monthly (or even weekly) survey.

- Invite individuals from every level of the organization to important meetings and events to help them grow their network.

- Dedicate time for self-reflection every day.

This is by no means an exhaustive list. The key to reducing or eliminating founder’s syndrome is openness and curiosity. Ask yourself how you can increase your exposure to new ideas, different opinions, and honest critique. And find ways to automate and institutionalize those feedback mechanisms.

How to Leverage Change Management for Your Business

A Final Reflection on Organizational Leadership

By actively pushing against behaviors and systems that foster founderitis and contribute to monoculture, you will create a more open, more innovative, and more profitable organization — one that you can truly take pride in.

After all, being humble still allows you to acknowledge great work, to be an expert and an authority and to lead a team or a client or a business. Humility is not synonymous with self-deprecation or being self-demeaning. C.S. Lewis spoke to this point in Mere Christianity when he discussed how the truly humble person “will not be thinking about humility: he will not be thinking about himself at all.” And the only way to begin to grasp this is by admitting first that you think of yourself too highly, for “if you think you are not conceited, you are very conceited indeed.”